Image copyright

Getty Images

Image caption

Greeks protest in Thessaloniki against the agreement on the name North Macedonia.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Image caption

Greeks protest in Thessaloniki against the agreement on the name North Macedonia.

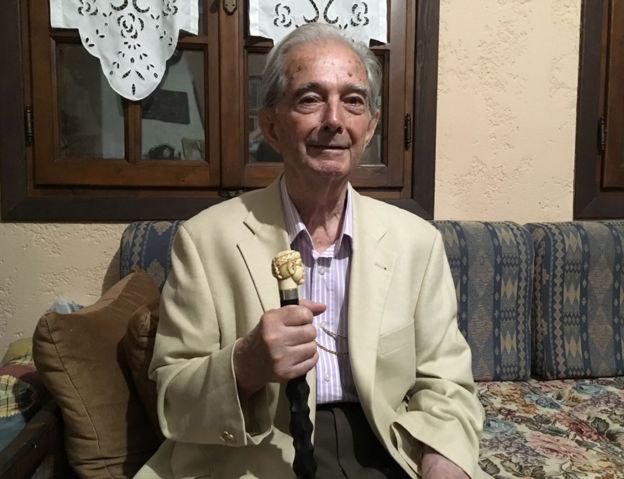

Mr Fokas, 92, stands straight as a spear in his tan leather brogues and cream blazer, barely leaning on the ebony and ivory cane brought from Romania by his grandfather a century ago. His mind and his memory are as sharp as his outfit.

A retired lawyer, Mr Fokas speaks impeccable formal Greek with a distinctive lilt: his mother tongue is Macedonian, a Slavic language related to Bulgarian and spoken in this part of the Balkans for centuries. At his son's modern house in a village in northern Greece, he takes me through the painful history of Greece's unrecognised Slavic-speaking minority.

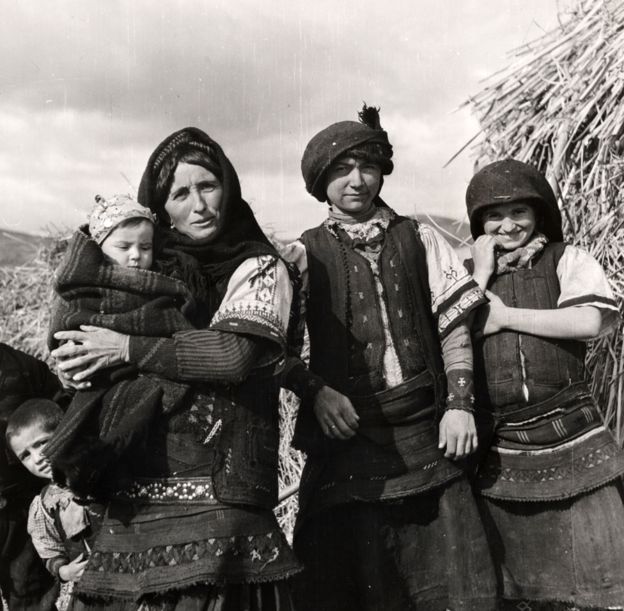

Most are reluctant to speak to outsiders about their identity. To themselves and others, they're known simply as "locals" (dopyi), who speak a language called "local" (dopya). They are entirely absent from school history textbooks, have not featured in censuses since 1951 (when they were only patchily recorded, and referred to simply as "Slavic-speakers"), and are barely mentioned in public. Most Greeks don't even know that they exist.

That erasure was one reason for Greece's long-running dispute with the former Yugoslav republic now officially called the Republic of North Macedonia. The dispute was finally resolved last month by a vote in the Greek parliament ratifying (by a majority of just seven) an agreement made last June by the countries' two prime ministers. When the Greek Prime Minster, Alexis Tsipras, referred during the parliamentary debate to the existence of "Slavomacedonians" in Greece - at the time of World War Two - he was breaking a long-standing taboo.

When Mr Fokas was born, the northern Greek region of Macedonia had only recently been annexed by the Greek state. Until 1913 it was part of the Ottoman Empire, with Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia all wooing its Slavic-speaking inhabitants as a means to claiming the territory. It was partly in reaction to those competing forces that a distinctive Slav Macedonian identity emerged in the late 19th and early 20th Century. As Mr Fokas's uncle used to say, the family was "neither Serb, nor Greek, nor Bulgarian, but Macedonian Orthodox".

In 1936, when Mr Fokas was nine years old, the Greek dictator Ioannis Metaxas (an admirer of Mussolini) banned the Macedonian language, and forced Macedonian-speakers to change their names to Greek ones.

Mr Fokas remembers policemen eavesdropping on mourners at funerals and listening at windows to catch anyone speaking or singing in the forbidden tongue. There were lawsuits, threats and beatings.

Women - who often spoke no Greek - would cover their mouths with their headscarves to muffle their speech, but Mr Fokas's mother was arrested and fined 250 drachmas, a big sum back then.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Image copyright

Getty Images

When Germany, Italy and Bulgaria invaded Greece in 1941, some Slavic-speakers welcomed the Bulgarians as potential liberators from Metaxas's repressive regime. But many soon joined the resistance, led by the Communist Party (which at that time supported the Macedonian minority) and continued fighting with the Communists in the civil war that followed the Axis occupation. (Bulgaria annexed the eastern part of Greek Macedonia from 1941 to 1944, committing many atrocities; many Greeks wrongly attribute these to Macedonians, whom they identify as Bulgarians.)

When the Communists were finally defeated, severe reprisals followed for anyone associated with the resistance or the left.

"Macedonians paid more than anyone for the civil war," Mr Fokas says. "Eight people were court-martialled and executed from this village, eight from the next village, 23 from the one opposite. They killed a grandfather and his grandson, just 18 years old."

Image copyright

Getty Images

Image copyright

Getty Images

Most of the prisoners on Makronisos were Greek leftists, and were pressed to sign declarations of repentance for their alleged Communist past. Those who refused were made to crawl under barbed wire, or beaten with thick bamboo canes. "Terrible things were done," Mr Fokas says. "But we mustn't talk about them. It's an insult to Greek civilisation. It harms Greece's good name."

Πηγή: